Southwest Airlines projects 6% capacity growth in CY2015 as long-haul from Dallas ramps up

20th November, 2014

© CAPA

Southwest Airlines is forecasting solid unit revenue growth in CY2015 as it joins the rest of its US airline peers in growing capacity year-on-year. The airline projects a 6% expansion in supply largely driven by increasing stage length as it capitalises on the lifting of long haul flight restrictions from its Dallas Love Field headquarters.

The airline believes it can drive unit revenue growth in CY2015 at the same rate as its projected capacity increase while decreasing unit costs between 1% and 2%.

All the US major airlines appear to be adding capacity at a faster rate in CY2015 than during the last couple of years, which is raising some concern that a supply-demand imbalance could occur.

But for now all the airlines including Southwest believe their expansion is justified, and do not feel any pressure to refine their projections.

The airline believes it can drive unit revenue growth in CY2015 at the same rate as its projected capacity increase while decreasing unit costs between 1% and 2%.

All the US major airlines appear to be adding capacity at a faster rate in CY2015 than during the last couple of years, which is raising some concern that a supply-demand imbalance could occur.

But for now all the airlines including Southwest believe their expansion is justified, and do not feel any pressure to refine their projections.

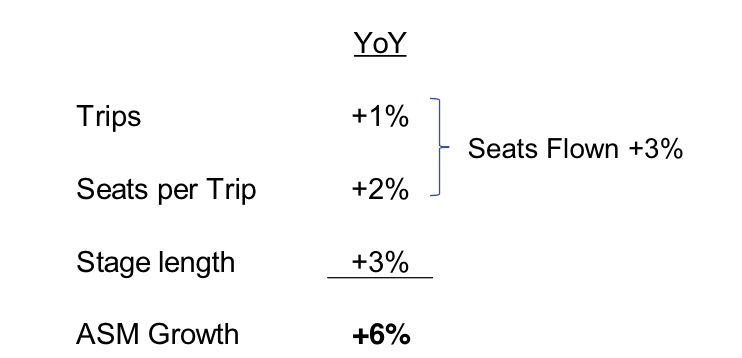

Longer stage lengths drive roughly half of Southwest’s planned ASM growth

Approximately half of Southwest’s forecasted 6% ASM growth in CY2015 is being generated by longer stage lengths

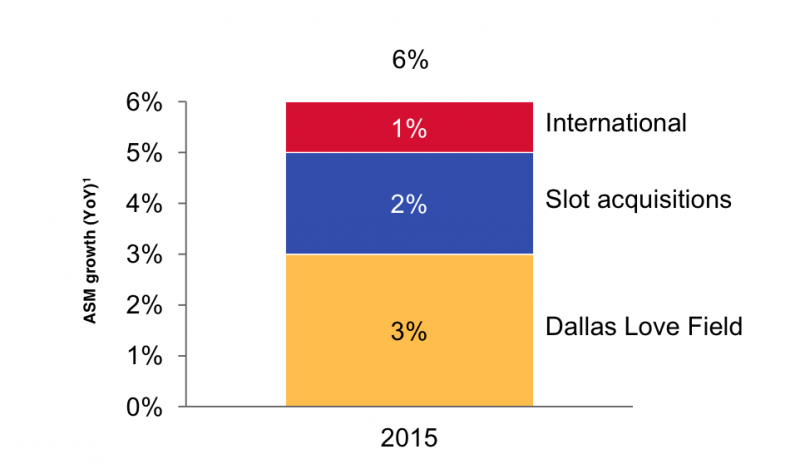

Southwest is resuming capacity expansion in CY2015 after keeping its supply essentially flat year-on-year in CY2014. During a recent discussion with investors airline CEO Gary Kelly predicted that for the next several years after CY2015, Southwest is likely to grow its US domestic capacity in the low single digits. Although Southwest is expanding its transborder service to the Caribbean and Latin America, international flights will still represent a fraction of its ASM deployment in CY2015 – roughly 1%. Approximately half of Southwest’s forecasted 6% ASM growth in CY2015 is being generated by longer stage lengths. With the full repeal in Oct-2014 of the Wright Amendment that prohibited certain long haul flights from Dallas Love Field, Southwest is adding service to key markets from its headquarters to 17 cities by the end of Nov-2014 (see background info).

Southwest Airlines CY2015 capacity projections broken out by trips, seats per trip and stage length

Southwest Airlines CY2015 capacity projections broken out by international, slot purchases and Dallas long-haul

Southwest estimates that its stage length from the airport will grow 70% year-on-year in CY2015

As a result of the new service from Dallas Love Field, Southwest estimates that its stage length from the airport will grow 70% year-on-year in CY2015. In early Nov-2015 Southwest remarked that the new markets from Love Field were recording load factors in excess of 90%. Some of that is no doubt due to promotions offered by the airline. Approximately 2% of Southwest’s anticipated capacity growth in CY2015 stems from slots it acquired at Washington National and New York LaGuardia airports that were divested by American Airlines in order to gain approval from the US government for the American-US Airways merger. Through a combination of obtaining slots from American and those held by AirTran, which it acquired in CY2010, Southwest now offers 33 daily roundtrips from LaGuardia and 44 from National.

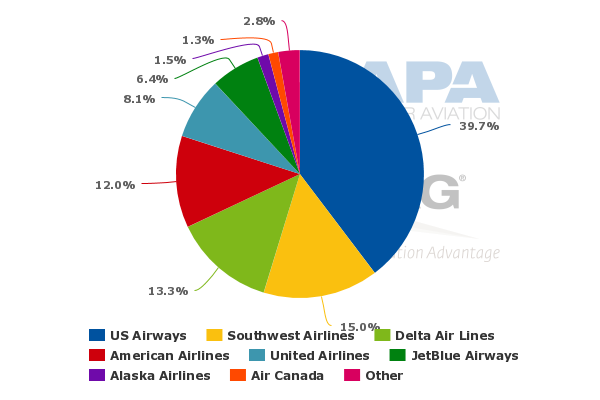

The airline highlighted it is now the second largest airline operating from Washington National, and data from CAPA and OAG show that for the week of 17-Nov-2014 to 23-Nov-2014 Southwest holds a 15% seat share at the airport. US Airways remains the leading airline with a nearly 40% share.

Washington Ronald Reagan National Airport capacity by airline (% of seats): 17-Nov-2014 to 23-Nov-2014

Spirit Airiines adds international flights from Houston ahead of Southwest

Southwest officially began operating international service under its own banner in CY2014, assuming routes operated by AirTran. Presently it serves San Juan, Cancun, Montego Bay, Aruba, Los Cabos, Mexico City, Nassau and Punta Cana. During CY2015 it is adding flights from Baltimore to San Jose, Costa Rica and is seeking approval for the launch of service from Orange County to Puerto Vallarta. Mr Kelly stated that Southwest should add two more international markets in CY2015.The airline should be revealing international destinations from Houston Hobby in the not too distant future as its new international terminal at the airport is scheduled for completion in late 2015. Ahead of the completion of the new terminal, Southwest plans to add service from Houston to Aruba in Mar-2014.

Spirit Airlines is also making an international push from Houston Intercontinental in CY2015 with the introduction of service to Los Cabos, Cancun and Toluca Mexico and the Central American markets of Managua, San Jose, San Pedro Sula and San Salvador.

United serves all of those market from Houston Intercontinental (operating to Mexico City instead of nearby Toluca), and Southwest no doubt has examined many of the destinations Spirit is adding ahead of Southwest’s international push from Hobby. It is not clear if Southwest considered an international expansion by Spirit from Houston as it was evaluating the market potential from Hobby; but Southwest may elect to add markets where it does not compete directly with Spirit.

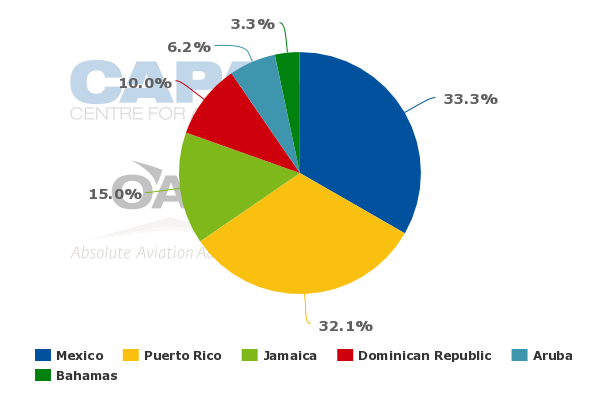

Presently, Mexico represents about 33% of Southwest’s international seat deployment

Presently, Mexico represents about 33% of Southwest’s international seat deployment, and previously the airline has stated its desire to see a full open skies agreement between the US and Mexico.

Southwest Airlines international capacity by country (% of seats): 17-Nov-2014 to 23-Nov-2014

Southwest projects a more normalised operating fleet in CY2015

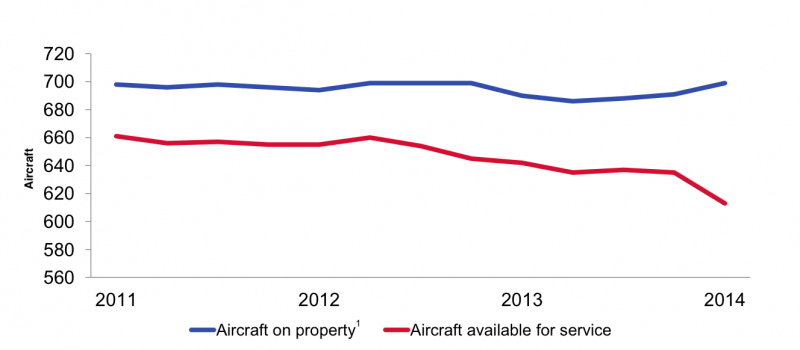

As its integration of AirTran comes to a close by YE2014, Southwest will move closer to a fully operational fleet. During the integration aircraft have been out of service for reconfiguration in the Southwest single class layout.Southwest estimates that during CY2015 it will have 20 fewer aircraft idle than in CY2015. As the aircraft return to operations, “we are generating a low cost capacity that will fund Dallas Love, Washington Reagan, New York LaGuardia and international,” Southwest CFO Tammy Romo recently explained to investors.

Southwest Airlines aircraft on property vs aircraft available for service: CY2011 to CY2014

Southwest sees some yield pressure in CY2014 from increased stage length

As Southwest joins other airlines in concluding that is planned capacity growth will be executed in an efficient manner, it does acknowledge that the higher stage lengths and roughly 20% of its markets under development until Apr-2015 “are a headwind to yields”, said Ms Romo. However, she concluded that Southwest will produce favourable margins “because we are funding this growth with minimal incremental cost through better fleet utilisation and fleet gauge”.Southwest believes it can generate unit revenue growth during CY2015 that is line with its projected 6% capacity increase. With yields being pressured from an increase in stage length, Southwest will drive some of its revenue growth by pushing higher loads. The airline explained that it is rotating some shorter haul routes out of Love Field that have lower load factors for longer-haul routes that could generate higher loads.

Fleet modernisation drives lower unit costs for Southwest in CY2015

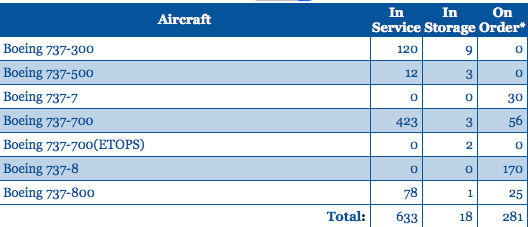

Southwest projects a 1% to 2% decline in its unit costs during CY2015 driven by increased aircraft utilisation and its fleet modernisation that entails phasing out its Boeing 737 Classic aircraft. CAPA’s fleet database shows that the airline presently operates 120 737-300s.

Southwest Airlines Fleet Summary as of 20-Nov-2014

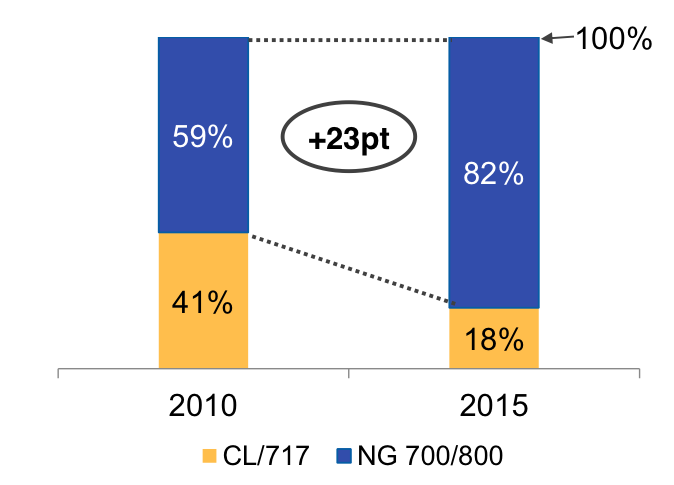

Percentage of 737 Classics and 717s in Southwest's fleet: CY2010 to CY2015

Southwest continually states that its goal is to broker deals with its employees that preserves its cost advantage, but during CY2014 cracks have emerged in the historically favourable relationship between management and employees.

Contract talks remain the big wildcard for Southwest

After missing its stated goal of achieving a pre-tax return on invested capital of 15% the last two years, Southwest is on a steady course to reach or exceed that target in CY2014. Its merger with AirTran, while taking some time to complete, has gone rather smoothly without creating a significant strain on its financial performance.The airline is confident of delivering a similar performance in meeting its ROIC targets for CY2015 as it adds more growth than it has during the last couple of years. It should be commended for maintaining its stature as one of the strongest US airlines measured by financial performance.

But the outcome of its labour talks remains a huge wildcard for Southwest, and more importantly, the airline needs to prevent any further deterioration of its employee relations.

Background information

Southwest new service from Love Field launched in 2014